Primary Colors for Orange

What food coloring colors make orange – Unlocking the vibrant world of orange is simpler than you might think! This journey into color mixing will empower you to create a spectrum of orange shades, from the softest sunset hues to the boldest citrus tones. We’ll explore the fundamental building blocks – the primary colors – that are the key to this captivating color.

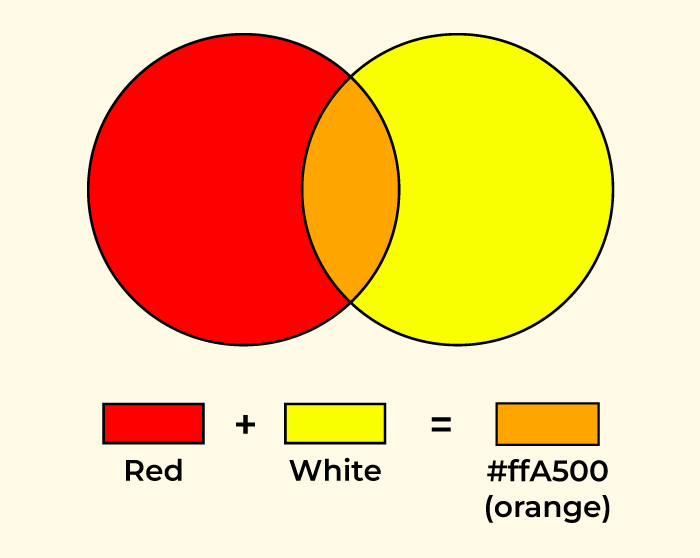

The secret to creating any shade of orange lies in the masterful blending of two primary colors: red and yellow. These aren’t just any reds and yellows; the specific shades you choose will dramatically influence the final orange you achieve. Think of it as a painter’s palette, where the subtle variations in your red and yellow pigments lead to a vast array of orange possibilities.

A deeper, more crimson red will yield a different orange than a bright, scarlet red when combined with the same yellow. Similarly, a golden yellow will create a different orange than a pale lemon yellow.

Red and Yellow Combinations for Orange Hues, What food coloring colors make orange

The ratios of red and yellow are crucial in determining the precise shade of orange. A higher proportion of red will result in a more reddish-orange, while a higher proportion of yellow will create a more yellowish-orange. Let’s explore some examples to illustrate this dynamic relationship.

| Red Food Coloring | Yellow Food Coloring | Ratio (Red:Yellow) | Resulting Orange Shade |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red-Orange (e.g., a reddish-toned food coloring) | Golden Yellow (e.g., a warm, slightly brownish yellow food coloring) | 2:1 | Deep, reddish-orange, almost terracotta |

| Bright Red (e.g., a pure, vivid red food coloring) | Lemon Yellow (e.g., a pale, light yellow food coloring) | 1:1 | Classic, vibrant orange |

| Crimson Red (e.g., a dark, purplish-red food coloring) | Sunflower Yellow (e.g., a rich, intense yellow food coloring) | 1:2 | Bright, yellowish-orange, almost gold |

| Scarlet Red (e.g., a bright, slightly bluish-red food coloring) | Canary Yellow (e.g., a pale, slightly greenish yellow food coloring) | 3:1 | A more muted orange, tending towards a peachy hue |

Secondary and Tertiary Colors Influencing Orange: What Food Coloring Colors Make Orange

We’ve explored the primary building blocks of orange. Now, let’s unleash the power of nuance! Just as a skilled painter uses subtle shades to bring a masterpiece to life, we can refine our oranges by introducing secondary and tertiary colors. These additions aren’t about drastically changing the orange, but about subtly shifting its character, its mood, its very essence.

Prepare to be amazed by the transformative power of a few carefully chosen drops!Adding small amounts of other colors to a base orange allows for a vast spectrum of variations. This isn’t about creating entirely new colors, but about enriching and modifying the existing orange hue. Imagine the possibilities – a softer, warmer orange, a deeper, richer tone, or even an orange with unexpected undertones.

This level of control gives you the ability to perfectly match your vision.

Effects of Brown and White

Brown, a tertiary color, adds depth and complexity to orange. A touch of brown creates a burnt orange, a color reminiscent of autumn leaves or spiced pumpkin. White, on the other hand, lightens and softens the orange, resulting in a pastel or peachy hue. Imagine a vibrant, almost neon orange gradually becoming a soft, delicate peach as increasing amounts of white are added.

The effect is a seamless transition, showcasing the versatility of color modification.

Effects of Secondary Colors on Orange

Introducing secondary colors – like green or purple – into our orange base presents a fascinating challenge and opportunity. These colors, formed by mixing two primary colors, possess a unique ability to shift the perception of orange in remarkable ways. A tiny amount of green, for example, can create a more muted, earthy orange, reminiscent of dried apricots or certain clay tones.

Achieving a vibrant orange hue when coloring food requires a blend of yellow and red food coloring; the exact ratio depends on the desired shade. This principle is perfectly illustrated when you’re dying easter eggs with food coloring , where experimenting with these primary colors allows you to create a range of beautiful orange tones for your festive eggs.

Ultimately, mastering the balance of yellow and red is key to any successful orange creation, whether it’s for Easter eggs or other culinary projects.

Conversely, a hint of purple adds a reddish-pink undertone, leaning the orange towards a coral or salmon shade. This is not about obliterating the orange but about subtly altering its character.

Visual Representation of Secondary Color Additions

Imagine three distinct swatches. The first is a pure, vibrant orange, the color of a ripe tangerine. The second swatch features the same base orange but with a subtle addition of green. This creates a noticeably less saturated, more subdued orange. The green subtly mutes the intensity of the orange, creating a warmer, earthier tone.

Finally, the third swatch shows the base orange with a touch of purple. This introduces a pinkish hue, shifting the overall tone towards a more coral-like appearance. The contrast between these three swatches highlights how even small amounts of secondary colors can dramatically affect the final color. The effect is a demonstration of the subtle artistry possible through color mixing.

Achieving Specific Orange Shades

Creating the perfect orange hue is an art, a delicate dance between red and yellow food colorings. The intensity and undertones of your orange depend entirely on the ratio of these primary colors and the specific brands you choose. Let’s explore how to achieve a range of orange shades, from the softest pastel to the richest, deepest tones.

Pastel Orange

Achieving a light, pastel orange requires a gentle hand and a focus on achieving a balance that avoids muddiness. The key is to use significantly more yellow than red, and to dilute the mixture with a generous amount of your base ingredient, whether it’s frosting, batter, or drink. A small amount of white food coloring can further lighten the hue and enhance the pastel effect.

Imagine a sunrise, soft and diffused; that’s the feeling you’re aiming for. For example, start with a 4:1 ratio of yellow to red food coloring, then gradually add more yellow until you reach your desired pastel shade.

Deep, Rich Orange

In contrast to pastel orange, a deep, rich orange calls for a bolder approach. This vibrant hue is achieved by using a higher proportion of red to yellow, while maintaining a balance to prevent the orange from becoming too brown or reddish. Think of a ripe clementine or a sunset over a fiery landscape; that’s the intensity we are targeting.

A good starting point would be a 2:1 or even a 3:2 ratio of red to yellow, gradually adjusting until the desired saturation is reached. The color should be intensely pigmented and full of warmth.

Brand Comparisons

Different brands of food coloring can yield surprisingly different results, even when using the same color and ratio. Some brands are more intensely pigmented than others; some have slightly different undertones (leaning more towards yellow or blue-red). For example, Brand A’s red might produce a slightly bluer orange when combined with yellow, whereas Brand B’s red might create a warmer, more golden orange.

Experimentation is key to understanding how different brands interact to achieve your desired orange shade. Keep detailed notes of your experiments, noting the brand names, color ratios, and the resulting shades. This will help you fine-tune your technique over time and achieve consistent results.

FAQ Compilation

What happens if I use too much red?

The orange will become too dark and possibly reddish-brown, losing its vibrancy.

Can I use gel food coloring instead of liquid?

Yes, but be aware that gel food colorings are more concentrated, so use smaller amounts initially.

How can I lighten a too-dark orange?

Gradually add small amounts of white or yellow food coloring until the desired shade is achieved.

Why is my orange turning brown?

This could be due to the food’s pH level or the use of old or low-quality food coloring.